On January 15th, the European Commission (the “Commission”) published its decision (the “Decision”) relating to the adequacy of the data protection offered by 11 countries.[1] The Commission upheld its prior adequacy decisions, which were adopted under the Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC), the General Data Protection Regulation’s (“GDPR”) predecessor. As part of the decision, it was announced that Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA”) continues to benefit from its adequacy status under the GDPR.

What does this mean for organizations doing business in Canada?

At a high level, this means that personal information can continue to flow into Canada from European countries subject to the GDPR without the need for other data protection mechanisms. However, it is not quite that simple.

Organizations that, for their own purposes or on behalf of their customers (i.e. service providers):

- Collect the personal information of individuals in the EU, as part of the offering of the businesses’ goods or services; or

- Are located in the EU and collect personal information, even if the processing of personal information is not within the EU,

can keep transferring personal information to Canada, without needing additional protections such as standard contractual clauses, as long as the recipient of the personal information is subject to PIPEDA.

This last point is important and often overlooked. The recipient organization in Canada must be subject to PIPEDA. This means that since private sector employee information is not covered by PIPEDA, businesses which are transferring their employee personal information to recipient organizations in Canada will need additional data protection mechanism (such as standard contractual clauses).

Examples of transfers of personal information could include:

- sending personal information to a service provider with storage facilities in Canada;

- a Canadian company collecting personal information from EU customers in order to fulfill their orders; or

- transferring personal information collected in the EU to a parent company located in Canada.

Organizations must remember that any onward transfer of that personal information to another jurisdiction must be assessed according to that jurisdiction’s status. For example, if an organization in Canada receives the personal information from the EU and transfers it to one of its service providers in the US, the organization must consider the adequacy standard of Canada and the protections it can implement for the transfer to the US (given only companies participating in the EU – US Data Privacy Framework have adequacy status).

Commercially, the adequacy decision is welcomed by businesses as it preserves and further encourages Canada’s trade relationships with the EU, however, the Commission’s decision may have other less obvious implications for Canada’s privacy regime (discussed further below).

What is adequacy and why does it matter?

Article 45 of the GDPR requires that transfers of personal data to another jurisdiction can take place, without any specific authorisation, where the Commission has given that jurisdiction “adequacy status”, in other words, has decided that the jurisdiction’s data protection regime ensures an adequate level of protection for personal data.

Canada’s adequacy status allows organizations to receive personal information governed by the GDPR without additional data protection measures such as standard contractual clauses, which are a set of standardised and pre-approved clauses that are incorporated into organizations’ contractual arrangements with other parties. These clauses often require that parties comply with a standard of privacy protection that is higher than what is required by legislation in those jurisdictions, which can be considered as a disadvantage during commercial negotiations.

Why is adequacy being evaluated now?

Under Articles 45(4) and 97 of the GDPR, there is a requirement for the Commission to reassess its adequacy rulings on an on-going basis, every four years, to determine if the countries continue to provide an adequate level of protection. Canada’s previous adequacy finding was issued in 2001.[2] The delay was caused in part by a requirement for the Commission to consider the implication of the Schrems II case, in which the Commission clarified the key elements to consider in the adequacy test.[3]

What is considered as part of the “adequacy” finding from the Commission?

Article 45 and Recital 104 of the GDPR list the criteria considered as part of adequacy decisions, and specifically note that these criteria are assessed with special consideration of “the fundamental values on which the Union is founded, in particular the protection of human rights”. These criteria include:

- how a particular third country respects the rule of law, access to justice as well as international human rights norms and standards and its general and sectoral law, including legislation concerning public security, defence and national security as well as public order and criminal law, and the access of public authorities to personal data;

- the implementation of legislation mentioned above, data protection rules, professional rules and security measures, including rules for the onward transfer of personal data to another jurisdiction;

- case law;

- whether there are effective and enforceable data subject rights and effective administrative and judicial redress for the data subjects;

- whether there is an effective functioning of one or more independent supervisory authorities, with responsibility for ensuring and enforcing compliance with the data protection rules, including adequate enforcement powers, for assisting and advising the data subjects in exercising their rights and for cooperation with the supervisory authorities of the EU member states;

- the international commitments the jurisdiction has entered into, or other obligations arising from legally binding conventions or instruments as well as from its participation in multilateral or regional systems, in particular in relation to the protection of personal data;

- whether the jurisdiction guarantees ensuring an adequate level of protection essentially equivalent (as opposed to requiring “equivalent” protection) to that ensured within the EU, in particular where personal data is processed in one or several specific sectors.

In its Decision, the Commission assessed, in relation to Canada:

- developments in the data protection frameworks since the adoption of the previous adequacy decision, particularly amendments to PIPEDA since 2001 (e.g., valid consent and breach notification), and the ongoing PIPEDA modernization efforts under Bill C-27 (discussed below);

- PIPEDA’s scope of application, noting in particular exemptions from the law, and the provincial and sectoral legislation that are considered as “substantially similar” to PIPEDA;

- The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s non-binding guidance (e.g., updates to the definition of sensitive information);

- The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s non-binding case summaries (on a variety of topics – e.g., right to deletion, international transfers of personal information);

- Oversight and redress available; and

- the rules in place relating to government access to personal information for law enforcement and national security purposes (e.g. constitutional considerations such as those under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Privacy Act considerations).

Impact of adequacy on substantially similar provincial legislation

Under Canada’s regime, the private sector privacy statutes in Quebec, Alberta and British Columbia have been deemed “substantially similar” to PIPEDA, and therefore those laws apply instead of PIPEDA for processing of personal information that takes place within the provinces. However, the substantially similar privacy laws have not received adequacy status.[4] Interestingly, the Commission’s decision indicates that “personal data transferred from the EU/EEA under the adequacy decision are considered cross-border data transfers, which are subject to PIPEDA”.[5] This is a curious assertion by the EU. PIPEDA is silent on the application of the law to cross-border flows of information. The CPPA, if passed, would update the application section to clarify that the CPPA applies in respect of personal information that is collected, used or disclosed interprovincially or internationally by an organization (s. 6(2)(a)), however the CPPA is not yet in force. The OPC’s non-binding guidance materials suggest that “all businesses that operate in Canada and handle personal information that crosses provincial or national borders are subject to PIPEDA regardless of which province or territory they are based in.”[6] Provincial privacy commissioners may take a different stance. In fact, guidance from the Quebec Privacy Regulator asserts that organizations located outside of Quebec that collect personal information as part of business in Quebec are subject to the provincial law.[7]

Impacts on Canadian privacy legislation development

The decision comes at a time when the government is advancing Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, legislative reform that would update and replace PIPEDA.[8] Regulators, industry, and privacy advocates alike have long claimed that Canada’s privacy laws have fallen behind, with the EU’s GDPR being the cited as the gold standard. Accordingly, adequacy has been a driving force for PIPEDA’s modernization. Unfortunately, PIPEDA’s renewed adequacy status may result in de-prioritization of Bill C-27 (the government determines the prioritization of Bills in the House). Likely to avoid de-railing Canada’s reform efforts, the European Commission explicitly called for Canada to continue to advance Bill C-27:

At the same time, the Commission recommends enshrining some of the protections that have been developed at sub-legislative level in legislation to enhance legal certainty and consolidate these requirements. The ongoing legislative reform of PIPEDA could notably offer an opportunity to codify such developments, and thereby further strengthen the Canadian privacy framework. The Commission will closely monitor future developments in this area.

Update on the Status of Bill C-27

The Commission’s decision casts a spotlight on PIPEDA’s reform, which provides a welcome opportunity to share an update on the status of Bill C-27. Bill C-27 was introduced and progressed through first reading on June 16, 2022. During second reading the Bill was discussed in the House of Commons on six occasions before being referred to the Standing Committee on Industry and Technology on April 24, 2023. There have been fifteen committee meetings to date, and more than 74 Privacy and AI expert witnesses have provided testimony to the Committee.

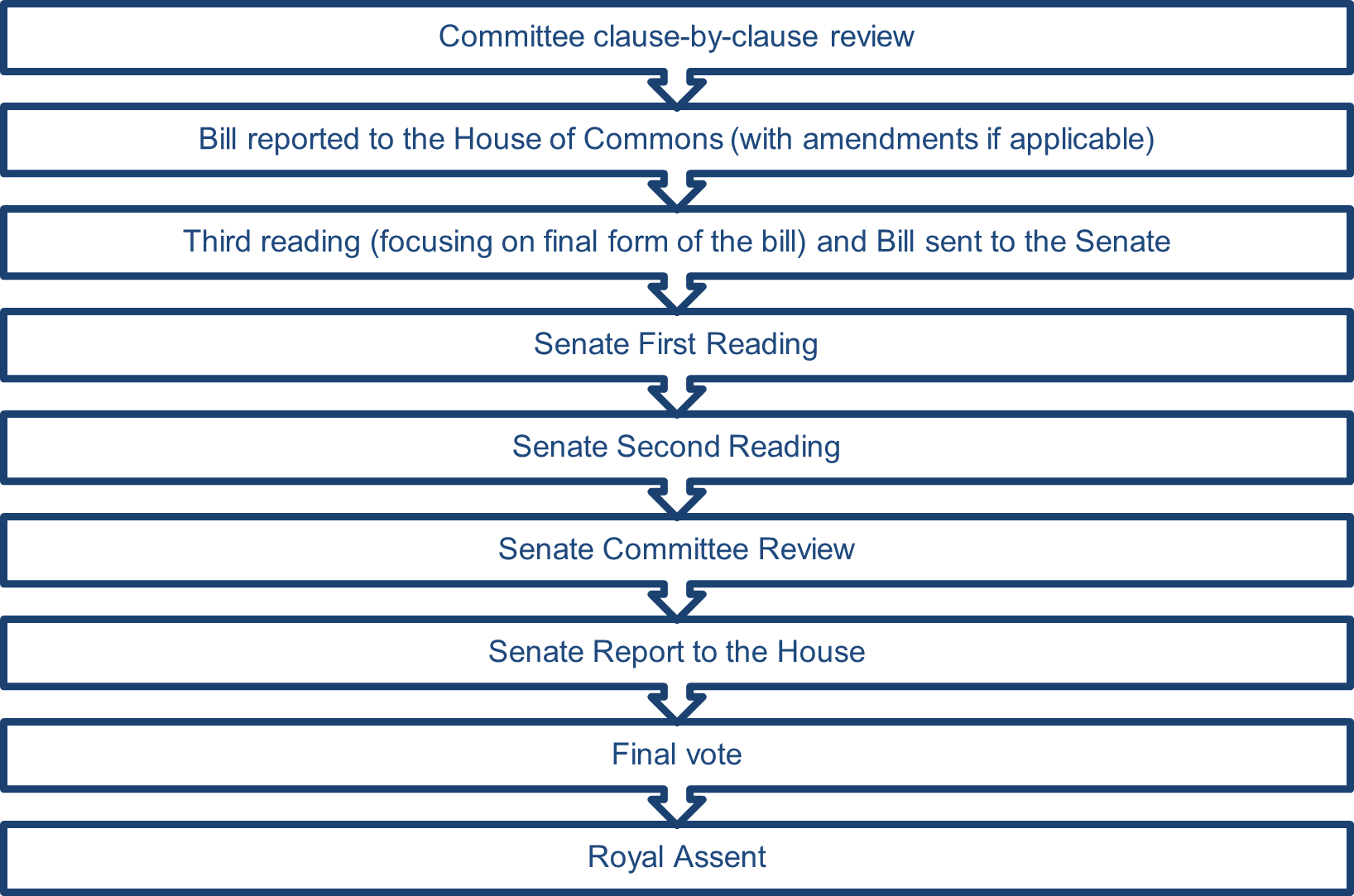

To become law, Bill C-27 must go through the following stages still remaining in the legislative process.

As discussed briefly above, whether C-27 will be prioritized by the government is yet to be seen. The House and Senate committees carry several files concurrently and have a lot of latitude in how they organize their work.[9] There is reason to believe Bill C-27 will continue to be prioritized by the Government. For one, Minister Champagne (the bill’s sponsor) has publicly shared his desire for Canada to act as a world leader on AI legislation.[10] There’s been much discussion about the appropriateness of coupling the privacy and AI acts in one bill, however the CPPA may benefit from the pairing – as advancing AIDA also means advancing the CPPA.

[1] The other jurisdictions receiving adequacy designation were Andorra, Argentina, Faroe Islands, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, Israel, Jersey, New Zealand, Switzerland and Uruguay.

[2] Commission Decision 2002/2/EC of 20 December 2001 pursuant to Directive 95/46/EC of the European

[3] Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Limited and Maximilian Schrems, Case C-311/18.

[4] In 2014 the EU issued a decision suggesting improvements to Quebec’s privacy framework before it could be deemed adequate: Opinion 7/2014 on the protection of personal data in Quebec.

[5] European Commission, “Commission Staff Working Document, Country reports on the functioning of the adequacy decisions adopted under Directive 95/46/EC”, see the top of page 58.

[6] Summary of privacy laws in Canada, Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

[7] Entreprises privées, Commission d’accès à l’information.

[8] Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, is comprised of three parts, the Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA), which would replace PIPEDA; the Personal Information and Data Protection Tribunal Act, which would establish a new Tribunal to oversea the CPPA; and the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (“AIDA”), which would create rules for artificial intelligence.

[9] https://www.ourcommons.ca/procedure/our-procedure/Committees/c_g_committees-e.html

[10] Standing Committee on Industry and Technology, Evidence, Number 086, Tuesday, September 26, 2023